Last Updated on December 27, 2024

An estate plan is one of the most important pieces of your financial life.

Are you sure yours is how it should be?

Does it have the right people in the right roles? Are your assets properly titled? Does it have common estate plan mistakes?

Do you even know what it says?

Despite it being one of the most important pieces of a solid financial plan, I frequently see mistakes in estate plans. I’m happy when I catch them, but I also hurt when I read stories about estate plans that have gone wrong after a death.

It’s easy to ignore your estate plan. I get it.

You do it and think you are good for the next 20 years, but that’s not the best approach. Life changes. Laws change. People around you change.

These changes require a careful review of your estate plan. I advocate thoroughly reviewing your estate plan at least once every five years even if it feels nothing has changed. Usually, something changes that may require a revision.

If nothing has changed, at least you will have a clearer understanding of what happens to your lifetime of savings after you pass away.

Let’s look at common estate planning mistakes and 7 questions you can ask yourself as you review your estate plan.

Do You Understand the Estate Plan?

I know an attorney drafted it. I know it’s probably in legalese. I know it’s most likely hard to understand.

You don’t want to rely on having told your attorney something once and assuming they have correctly understood what you have said.

Have you ever seen kids play the Telephone Game?

It’s a game where kids form a line or circle and one kid whispers a message into the next kid’s ear. That kid then repeats it to the third person in line. They continue down the line and when it gets to the last person, they say the phrase out loud for everyone to hear.

Everybody gets to hear how much the phrase has changed.

And let me tell you, it’s often nothing like the original phrase!

I remember as a kid that the phrase could change with the second person, meaning even the second person couldn’t repeat back what they just heard.

That’s what can happen if you tell your attorney something once and assume they correctly understood you, correctly wrote it down, and correctly drafted what you wanted.

Even the best attorneys will miss important information. I know as a financial planner, I often ask people to repeat things or paraphrase what I’ve heard back to clients to ensure I understand. It’s normal in professional conversations and with friends and family.

My recommendation to help make sure you understand your estate plan is to print it out and read it all the way through. I find I catch more errors on paper than reading on the computer screen. Write next to any paragraph or word you don’t understand. Go through it with your attorney. Your attorney should be able to explain any sections you don’t understand.

Will it cost more?

Probably, but you know what will potentially cost even more?

You pass away and your estate plan does not reflect what you wanted, which costs your heirs more time, pain, and money than they anticipated.

I’m not an attorney, and I don’t give legal advice, but I’ve gone through estate plans with people before to help them understand what I see in the documents.

Often, it’s not what I am seeing that’s the most helpful, but taking the time to actually go through the documents. Wills, powers of attorney, and other parts of the estate plan can be long, which makes it difficult to commit the time to review them.

If you have a family member or friend you are willing to share yours with, set a time with them to go through each other’s. If you work with a financial planner, see if they will review it with you. Having an accountability partner can be helpful.

Are the Right People in the Right Roles?

I often hear something along the lines of, “I made my Will 20 years ago. I should probably review whether it makes sense to have Mary be my executor. She is 10 years older than me.”

Remember how I said life changes?

Life changes. People get older. People move away. People die.

When I say “the right people in the right roles”, I am primarily talking about guardians, trustees, agents (powers of attorney), and executors.

If someone needs a guardian, such as a child or an adult who lacks capacity, is the person you named still the right fit?

Are they local or would they relocate? Do they have the time and willingness to do it? Do you have backup people or organizations named in case the first person is unwilling to serve?

Something I commonly see is for people to name one or two close family members for a role, and that’s it.

If you only name one person and you happen to get in an accident with them and you both die or that person passes away a year prior and you forget to update your estate plan, you now are leaving it to state law and the courts to decide who is appointed to the key roles in your estate plan.

I prefer naming a few people and even potentially a professional trustee or executor as the final back up in case the extreme unlikely event occurs where everyone dies before me.

Also, know that serving as an executor is a thankless job. It’s a time-consuming administrative process with personal liability exposure.

I once knew an attorney who joked, “Which kid do you like the least? Name them as an executor.”

It was only a joke, and typically, people name their most responsible and organized family member or friend. Before you do, ask yourself if they have the capacity to take on such a large, thankless role.

If you have multiple backup people in each role and you are comfortable with the people you named, you are usually in good shape. It doesn’t usually take more than 15 minutes to skim through who you have listed and see if updates are needed.

Does it Allow for a Disclaimer Trust?

This is a big one.

It’s not only important to ensure your estate plan allows for a disclaimer trust, but also that you understand it. This is one of the most common things I explain to people because most don’t understand the benefit.

A disclaimer trust is a provision within a Will that allows a trust to be established and funded upon your passing. It does not force a trust to be established, but gives someone the option of establishing it.

This is helpful because a surviving spouse may not want to fund a disclaimer trust at death. With a credit shelter trust or bypass trust, the funding is usually not optional. A disclaimer trust allows for more flexibility. If you are remarried and have children from prior marriages, this may not be the best approach because you may want to force certain actions to happen.

A disclaimer trust is beneficial because assets that go into it are not included in the estate when the surviving spouse passes away. Plus, the disclaimer trust can provide income and other support for the surviving spouse while alive.

It’s a way of reducing future estate tax consequences while still being able to benefit from the assets.

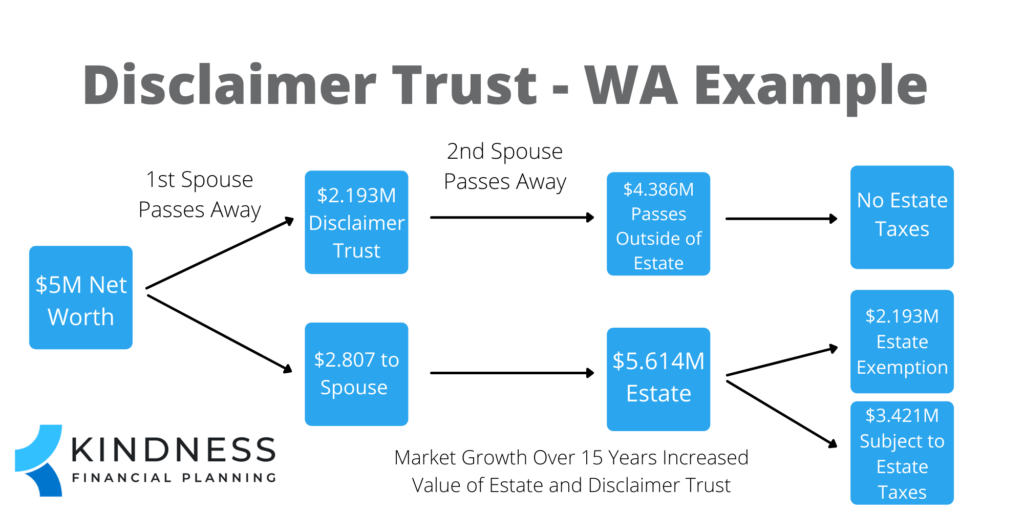

For example, I lived in Seattle, WA for a good part of my life, and Washington State has a $2,193,000 exemption amount. This means each person can die with $2,193,000 and owe zero in estate taxes. When you have an estate valued above this amount, you face a Washington State estate tax ranging from 10%-20%.

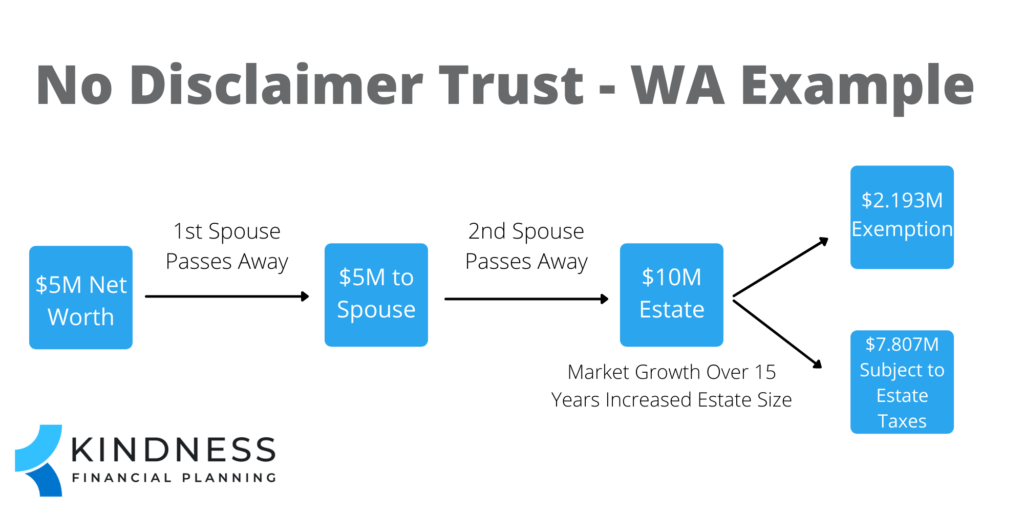

You can see how a disclaimer trust helps below.

If you allow all assets to pass to the survivor and choose not to fund a disclaimer trust or don’t have the provision in your Will that allows for it, it can mean significantly more in estate taxes later.

In this hypothetical example where you start with $5M and it grows to $10M over 15 years, it means $4.386M more is subject to estate taxes.

That’s $800k more in estimated estate taxes for not taking advantage of the disclaimer trust.

This is a simple example with simplified assumptions of how assets grow, and your individual situation likely won’t look exactly like this, but it gives you an idea of how a disclaimer trust can be helpful to reduce estate taxes.

Are Your Assets Appropriately Titled?

One of the most common estate plan mistakes I see people make is create a trust, but forget to actually fund the trust.

They go through a lengthy process of creating a trust that carefully takes into account their wishes, but then assets are not retitled, effectively negating the careful planning they did.

If you create a trust, did you actually fund the trust? Are your brokerage accounts titled in the name of the trust? Are your bank accounts titled in the name of the trust? Did you deed your house into the trust?

If you created a trust, review which assets should be in the trust. If they are not in the trust and should be in it, work on putting them into the trust.

Another common estate plan mistake I see is making children joint owners on accounts or a house to simplify things when they pass away.

This can be a HUGE issue.

Not only are you potentially creating a gift if you make them a joint account holder (and a gift tax return may need to be filed), but you are potentially eliminating the possibility of them receiving a step up in cost basis at your death.

When someone passes away, their heirs usually inherit property with a cost basis equal to the fair market value at your death. What this means is if you bought stock at $10 many years ago and you pass away when it is worth $100, your heir’s cost basis will be stepped up to the $100. They could then sell the asset with minimal tax consequences.

However, if you gift them an asset by making them a joint account holder, only your proportional share of the account will receive a step up in cost basis – not the full account. This means your child would end up paying more in taxes when they sell the asset because they would have a lower cost basis.

It’s usually better to add a transfer on death or payable on death designation to an account instead of making a child a joint account holder to simplify the process at death. If a child needs control, it’s usually better to add them as a power of attorney to the account.

Plus, if you make a child a joint account holder, you face more liability. If your child is sued or defaults on debts, the account you made them a joint account holder on could be taken in a lawsuit or to fulfill a creditor’s claims.

There are very rare circumstances where it makes sense to make a child a joint account holder later in life.

It’s important to review your assets every few years to ensure they are properly titled. You don’t want to accidentally open a new account in your name, fund it later with significant assets, and then find out you forgot to title it in the name of the trust.

Are Your Beneficiaries Accurate?

In addition to “are your beneficiaries accurate?”, do you know which beneficiary designations supersede others?

What I mean by that is that many people commonly think, “Oh, I have everything figured out in my Will. It doesn’t matter what my retirement account beneficiary says.”

It does matter.

Your retirement beneficiary supersedes your Will. If your retirement beneficiary says 100% of the account goes to charity and you put 100% of your retirement accounts go to your friend, Jane, in your Will, they will go to charity.

Also, if you don’t put a retirement account beneficiary, the tax consequences can be less favorable to your heirs. There are situations where it makes sense for your estate or trust to receive retirement funds at death, but for most people, it’s usually better to name them directly as a beneficiary.

People need to be very careful in how they list beneficiaries on retirement accounts, whether they use transfer on death designations, and how to coordinate it with their Wills or Trust.

On top of that, make your beneficiaries as tax-efficient as possible.

If you want to give to charity, I normally recommend naming a charity as an IRA beneficiary. The charity receives the funds and pays no income tax, whereas a family member or friend would.

It’s usually better to have Roth IRAs or taxable brokerage accounts go to family and portions of IRA accounts go to charity.

I commonly see individuals list family as IRA beneficiaries and put in their Will that a charity will receive $50,000 of the residuary estate. Although it’s not bad, it’s not the most tax-efficient strategy.

Lastly, have you accounted for situations where a beneficiary passes away before you?

For example, if you have three children and all three children have two kids, what happens if one of your three children pass away before you?

Does your Will state that the remaining funds go to your other two children? Or do they go to your two grandchildren?

What about your retirement beneficiaries? What does it say in that scenario? And your life insurance?

The challenging part of estate planning is anticipating many different scenarios, being as specific as possible, but also leaving room for flexibility when life happens.

Review your beneficiaries and think about different scenarios to see if your beneficiaries are accurate and setup to be as tax-efficient as possible.

Could it Be Simplified?

An estate plan can allow you to be almost as specific and complicated as you want.

The problem is that complexity usually adds difficulty. It also usually allows less flexibility as life happens.

If you state that your childhood home can only be sold if all your children own a home, what happens if one of your children does not want a home?

If you state that a child does not receive their full inheritance until age 65, what happens if they have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to go to school or buy a business that could drastically improve their life, but can’t afford it?

If you state all children must own the vacation house together, but one never uses it and has to pay for it while the others love it and use it regularly, how will that affect sibling dynamics?

Life can get complicated. You can add all the asterisks you want to your plan, but the more you add, the more likely it is for your plan to not work as intended.

Although there are certain situations where more restrictive rules can be helpful, I find simplicity is usually better.

Are you Aware of the Estate Tax Consequences?

Although many people are not exposed to the Federal Estate Tax, which is at $13,990,000 per individual in 2025, many people are exposed to their state estate tax. Eleven states have an estate tax: Hawaii, Washington, Oregon, Minnesota, Illinois, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, Maine, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Five states have an inheritance tax: Iowa, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Maryland has an estate and inheritance tax.

This means 17 states and the District of Columbia may tax your estate.

Some states have low estate tax exemptions. Oregon is such a state at $1M, meaning they start taxing your estate if you have more than $1M.

It’s important to be aware that your estate typically includes everything you own: your home, life insurance death benefits, cars, brokerage accounts, retirement accounts, bank accounts, business, etc.

For many people living in states with low estate tax exemptions amounts, it can be easy to cross that threshold.

If you anticipate being subject to estate taxes, understand how your plan accounts for paying the taxes and how it might affect your other beneficiaries. If your assets are largely illiquid, such as in a business or real estate, how will the estate taxes be paid?

Do you have mostly retirement accounts? If those are liquidated, income taxes may be due in addition to the estate taxes. Know how that will reduce the amount going to your heirs.

It’s also good to discuss whether gifting assets, either to family, friends, or charity, during life makes sense to reduce the value of your estate. You can also discuss whether it makes sense to make a larger gift to charity during your life, such as to a charitable remainder unitrust (CRUT), that can provide income during your life and then the remainder goes to a charity at your death.

Although facing the issue of paying estate taxes is a good problem to have, don’t approach it passively. There are many strategies that may reduce your estate tax exposure. Planning earlier may give you time to properly implement the strategies.

Final Thoughts – My Question for You

Since estate planning is something we only do a few times in our lives, it’s difficult to make sure it’s what we intended. Add the fact that most attorneys use jargon that make it more difficult to read, and it’s no wonder many people are unsure of what is in their estate plan.

An estate plan should be reviewed more frequently than every 20 years. When major legislation happens, that’s a good time to review your estate plan because it may be impacted. Anytime a significant life change happens, I recommend reviewing your estate plan.

As you go through it, ask yourself the following questions:

- Do you understand the estate plan?

- Are the right people in the right roles?

- Does it allow for a disclaimer trust?

- Are your assets appropriately titled?

- Are your beneficiaries accurate?

- Could it be simplified?

- Are you aware of the estate tax consequences?

I’ll leave you with one question to act on.

When are you going to review your estate plan?