My dad died in July of 2023.

These are the 9 lessons I learned about death and money during his 7 year battle with Stage IV Lung Cancer, increased cognitive impairment, relapse after 20 plus years of being sober, his death, and life post-death.

As a financial planner, I’m privileged to be alongside people as they experience death in their own lives. I hear what it’s like and help people plan to make it easier on their survivors.

I’ll borrow a bit from my work and incorporate themes I’ve seen in my career, but most of this is my first hand experience, including fighting the healthcare system, how the legal system is not well set up for aging, and tips you can take to make it easier on your loved ones.

Lesson #1: End of Life Care is Lousy

Unless you get extremely lucky with a saint of a caregiver, end of life care is lousy. It doesn’t matter if you hire an elder care consultant and have $20,000 per month to spend or are on Medicaid.

There are very few good places to live as you age.

You can choose to age in your home, but then you must figure out how you can bring care into your home.

For some people, that means family members. Perhaps a daughter or son, though usually a daughter, will quit their job or go part-time to provide care. Unfortunately, many people don’t realize how challenging it can be to give up a paycheck and how difficult it can be to go back into the workforce after being out of it for years.

It’s a lot for a family member to shoulder, whether you ask or they volunteer.

If you prefer to hire care in your home, then you must find a caregiver or agency who can meet your needs. Then, you may run into issues if a caregiver gets sick or can’t make it. Who can cover for them?

If you hire a private caregiver, you may go without care or a family member may need to leave work to help.

If you hire an agency, they may be able to send another caregiver, but they may be short staffed.

Aging in place at home is often people’s wish, but it’s a much more difficult and expensive reality than people realize. If that’s a wish of yours, call a caregiving agency and ask what it would cost for a few hours a day, 8 or 10 hours a day, and for full-time care. A few hours a day a few times a week might be a couple thousand dollars per month, but more full-time care can often be over $20,000 per month.

In my dad’s case, we went through a few different caregiving agencies because he either fired them or they fired him for his erratic behavior.

Even if you can find care, your loved one’s behavior, whether medically related or not, may destroy your carefully crafted plans. We paid between $30 and $40 an hour for my dad’s care at home. When it was a few days a week in the afternoon, it was fine.

When he wanted to stay at home after being discharged from the hospital and needed more full-time care, it was not financially feasible. It would have been over $10,000 per month.

If you decide an assisted living facility or an adult family home is a better solution, you don’t have to solve for how to hire care, but you still run into issues.

Many of the prices you see advertised are base prices and don’t include higher levels of care, such as administering insulin for diabetics, help with showering, or other daily needs.

For example, when we looked at assisted living facilities for my dad, the base fee was $4,500 per month, but then his care assessment was 36.25 points, which meant an additional $2,175 per month.

You can see in the image below showing how they assign points based on what services are needed. For example, his medication assistance was 17.75, which added the most points and increased the cost significantly.

Although they did a preliminary assessment and had access to his medical files, he had an outburst and was kicked out of the facility in less than 48 hours. With move-in fees, that 48 hour stint cost over $5,000.

When my dad finally failed at home again and was hospitalized for a few months, placement was challenging.

The hospital found an adult family home where the first question they asked me when I got on the phone with them was, “He is private pay, correct?” No “Hello, how are you?” or anything.

Straight to the money.

The money hungry adult family home was $7,000 per month.

Like most places, my dad liked some caregivers, but not others. The adult family home was not well run. The issues ranged from:

- Not opening their mail and claiming they did not receive the monthly rent payment. This went on for 3 months.

- Not checking the medication list after hospital discharge and my dad going off critical medicines (mood stabilizers and Creon, which allowed my dad to digest his food).

- Not creating a care plan (requirement by the state).

- Serving pork even though they were made aware that my dad did not eat it for religious reasons.

- Unbalanced meals, such as white bread with packaged meat and a slice of cheese for lunch.

My dad had many things working against him, but I know people who have paid $15,000 or more per month and care is still worse than we would want for our loved ones.

I’ve learned money can help with the care you receive, but we are not set up for aging in this country. It’s an ugly process.

Lesson #2: Simplicity Makes Life Easier

I’ve learned simpler is better when it comes to finances.

This can mean many things, but one of the easiest steps is consolidating accounts to as few accounts as possible at one custodian.

For example, I met someone recently who had 13 accounts across 5 custodians and could consolidate to 7 accounts at 1 custodian.

The more custodians, or financial institutions, where you hold your assets, the more paperwork and phone calls a loved one needs to make after your death. It’s one more process you need to learn and hope the account was titled correctly or the proper beneficiary was on file.

My dad had one bank account when he died.

What a blessing it was to walk into that bank with a death certificate and complete their paperwork.

That was it. One meeting, less than an hour.

I’ve sat on hold with people calling five different financial institutions to learn what is needed to process accounts after death. It’s an unnecessary burden in most cases.

After they sit on hold, they must complete different sets of paperwork to set up an estate account or distribute money to beneficiaries.

Then there is the issue of tax reporting forms the year after you die. Your loved ones still need to track down those forms from every financial institution.

Want to provide your loved ones with a gift?

See how few accounts you can have, double check the titling and beneficiaries, and let them know who to call if something happens to you.

This may seem incredibly simple, but it’s one of the most impactful things you can do.

Lesson #3: Boundaries are Important

When it comes to aging and death, boundaries are important.

It’s not a child, family member, or friend’s responsibility to provide endless care, give up a career, or drastically alter their lifestyle.

You get to make the choice of what you want to do.

All of them are fair.

Want to help out one hour per week? That’s okay.

Want to help out 10 hours per week? That’s also okay.

Want to move in to help? That’s okay too.

It’s a slippery slope when someone is getting older.

Help may start as grocery shopping once a week and before you know it, you are paying bills, finding caregivers, taking them to medical appointments, refilling their medications, and more.

In my dad’s case, it started off with simply going to medical appointments to help be an advocate.

That was easy enough, but then it became communicating with the hospital, fighting against discharge, arranging for caregivers, completing paperwork to get into assisted living, and more.

Everything was urgent and last minute. Nothing was planned.

It sometimes meant giving up a work day. Other times, it meant flying across the country and rescheduling appointments.

It’s okay to set boundaries. You don’t need to do it all, nor should you be expected to do it all.

My mom and I both stepped back from caregiving at different times in our seven year journey and told my dad he was on his own.

Was their guilt and tears around it?

You bet. But, it was still the right choice.

Mentally, we couldn’t do it anymore. We were finding ourselves broken, depressed, and aggravated.

We couldn’t show up well for ourselves or for those in our lives because we used all of our energy trying to care for my dad.

Set the boundaries and don’t let the goal post keep moving.

Lesson #4: Prepaid Burial Arrangements are a Gift

I had never been a big fan of prepaid burial arrangements until I used the one my dad paid for.

I wasn’t a fan because it tied up money, and you always had the uncertainty of where you would die. For example, if you moved away from the funeral home you contracted with, you may need to pay expensive fees to get a body to the funeral home.

For this reason, I’m still not a fan if you are younger and anticipate moving, but for people who are in their 80s or have a terminal illness, prepaid burial arrangements can be a huge blessing.

In my case, my dad paid for one a few years before he passed away. He completed the paperwork, paid for what he wanted, and when he died, I simply had to contact them.

They arranged the rest.

I felt grateful that it was one less piece of paper to complete, one less thing to pay for, and I could focus on grieving.

Lesson #5: Springing Durable Power of Attorneys (DPOAs) Can Be Useless

Many people are unfamiliar with how their durable power of attorney works. Unfortunately, what sounds nice in the legal world may not work so well in the real world.

I find this to be the case with springing durable power of attorneys.

A springing durable power of attorney is typically not activated or effective until two physicians declare someone incompetent.

In the case of a coma or other extreme health event, that’s easy to determine. If someone is in a hospital bed unable to communicate or pay their bills, many physicians will probably have no problem declaring them incompetent.

The issue is that as people age, cognitive impairment often becomes an issue.

The lines are not so clear between competent and incompetent.

Many physicians will err on the side of caution and say someone is competent.

We ran into this issue at the hospital multiple times where they kept wanting my sign off on where he would go after discharge, but kept saying he was competent to make his own decisions. I kept putting it back on them that there was no use making a plan with me if they were ultimately going to listen to my dad. In my dad’s case, he was refusing most placements and wanted to be discharged home.

Their definition of being competent was basically a person’s orientation. It’s typically noted as oriented AOx4 (alert and oriented x4). In my dad’s case, he usually knew who he was, where he was, sometimes the date, and what was happening around him.

But, he couldn’t pay his bills, had no food in the fridge, was not taking his medications, and was hospitalized due to his own neglect.

Yet, he was “competent” most of the time. I disagree with their definition of competent and other healthcare professionals I know also disagree, but that was their decision.

Thankfully, my dad did not have a springing durable power of attorney, which meant I could add myself as the DPOA on his bank account and help with his finances.

When we discovered a box of bills that were unpaid at his house, I paid them. I didn’t need to go to a physician to try to prove that he was incompetent.

When I needed to pay his landlord, the DPOA allowed me to talk with his landlord and pay him.

When we needed to get my dad a new phone because he lost it in the hospital, I could set up a new phone for him.

The only reason we could do it was because my dad’s DPOA was effective when he signed it. Had it been springing, it would have created an even bigger mess I would have had to clean up after my dad died.

Springing durable power of attorneys add extra burden to your loved ones during an already challenging time. Plus, you might not be “incompetent enough” for them to be activated even though you need help.

In my dad’s case, any rational person would have looked at the situation and said he was incompetent, but many medical providers do not want to risk being sued saying someone is incompetent.

Lesson #6: Attorneys and Accountants are Worth It

I’m a financial planner, and I’ve been through the death process many times in my career.

I generally know how it’s going to go, landmines to watch out for, and how much time it’s going to take.

I still hired an attorney when my dad died to address specific questions I had around his estate and medical debt.

It cost a pretty penny, but it was 100% worth it.

Yes, you can go through the probate process on your own and navigate everything as the executor without legal help, but why would you?

Why not pay someone to take some of that burden off your shoulders? They do it regularly, help save time, and can help you potentially reduce liability by doing something incorrectly.

I’ve seen people try to settle estates on their own. It isn’t pretty, and I often see it done incorrectly.

If my dad had a more complicated financial situation, I would have hired an accountant to do his final tax return and advise on estate filings. I did it myself because he only had Social Security income and a bank account.

I hire when it makes sense, such as for my own personal financial situation. I hired an accountant for my wife and I. Could I do it? Sure, but it’s not something I want to do, and it has become more complicated over the years.

I didn’t include financial planners in the title, but a good financial planner is also worth it. In my dad’s case, I didn’t hire a financial planner because it was simple, and I am a financial planner.

I’ve helped many people through the process after a spouse or relative dies. It can be beneficial to have a sounding board and a financial planner to help walk through the process.

Lesson #7: Processing Loss with those on the Journey is Helpful

One of my favorite conversations after my dad died was with the eldercare consultant we hired to help us navigate my dad’s difficult behavior.

My mom and I invited her to coffee while I was in town simply to say thank you. She had been a saving grace.

She was one of the few people who really ever got to know my dad. Over his life, my dad never let many people in, so it was healing to reflect on the times we had been through together.

I even had the courage to ask her, “Out of all your years doing this, is my dad in the top 10 of the most difficult clients?” She told me he was definitely in the top 5.

It was nice to hear that our constant battles over the past seven years with my dad were somewhat unique.

She told us stories about him, and it was good to reflect, laugh, and feel what we had been through.

If you have the desire, invite those that have been on the journey with you to coffee. When my dad died, I appreciated hearing about the good times friends or family had with my dad, particularly because most of my more recent memories of him were negative.

It was a reminder that although he had made our life a living hell frequently in the past seven years, he did help others and had a positive impact at times.

Lesson #8: Inheritances are Strange, Even if a Financial Planner

I knew from the moment my dad was diagnosed my inheritance would fall between $0 and a few hundred thousand dollars. It was a wide range because we didn’t know what his care would look like and how much it would cost.

Near the end of his life, it was starting to feel like he would go on Medicaid and we may need to pay out of pocket for some of his expenses.

In the end, I received an inheritance.

You would think a financial planner would be unbothered by an inheritance.

Nope.

I’ve heard concerns and feelings around inheritances. I’ve worked with people who have received inheritances. It’s an everyday thing in my line of work.

That’s why I was so surprised about the feelings I had when I received it.

Here were a few things that came up:

- I wanted to deal with and be done with it ASAP.

- I felt guilty about receiving it.

- It took planning to decide what to do with it.

The inheritance felt like one of those “out of sight, out of mind” situations. Inheritances require careful planning because research has shown people don’t make the best decisions with large sums of money received at once, but I wanted to deal with it and move on.

It felt like if I did something with it, I wouldn’t have to process my emotions around it.

Which brings me to how I felt — somewhat guilty.

It’s strange receiving a chunk of money when someone dies. My inheritance was not a life changing amount of money for me at this stage of life. It would have been when I was younger, but it didn’t impact our daily living.

I don’t know how else to put it other than receiving money because someone died can feel strange.

In my experience, many people treat that money differently, sometimes as a “separate bucket”, but at the end of the day, it’s your money. It is like any other money in your bank or investment account. Treating it differently is generally not a good idea.

It can lead to riskier or foolish decisions because you may treat it like it’s “bonus money” that you didn’t have before.

My mom has always been a big advocate of splurging on something special if you receive a gift or inheritance, and I did that.

I like to cook and I appreciate good, sharp knives in the kitchen. I ended up buying a few knives, which I figure my dad would have appreciated since he loved cooking.

Beyond the small splurge, I talked with my wife to see if we needed this money for any upcoming life changes. Again, it was a strange conversation because here is money we never expected to have that we suddenly received.

We didn’t need it for anything, so I invested it. It’s now part of our long-term financial independence plan.

A note on life insurance: If you need life insurance, don’t be the person who decides not to purchase it.

Unfortunately, I see many people who could have afforded life insurance, choose not to buy it, and a surviving spouse needs to drastically change their lifestyle after death. It’s an unnecessary burden.

Lesson #9: Grief is Unique

There are often patterns in grief, but everyone’s situation is different.

I had a lot of anger up until my dad’s death for what he put us through during life. The moment he died, there was nobody to be angry with anymore. The anger faded almost instantly.

I still occasionally get angry, but for the most part, there is only the feeling of, “I wish it had been different.”

I sometimes mourn the loss of my dad, but after seven years with a terminal illness, I did most of my grieving prior to my dad’s death. Between the cognitive impairment and other health issues, he hadn’t been the person I knew for a very long time.

How someone feels day-to-day will vary based on their relationship, what is happening in their life, the situation in which they died, as well as other factors.

Don’t assume you know what someone is going through.

Don’t say “at least…” followed by something to try to make them feel better, such as “at least you got to spend time with him.”

Don’t assume there is grief when there may be other stronger emotions present.

Instead, ask about a memory with their loved one.

Ask about what they were like as a person.

Ask for a funny story involving their loved one.

People generally want to talk about their loved one. They don’t want to hear “I’m sorry for your loss” one more time followed by an awkward silence or them trying to make you feel better.

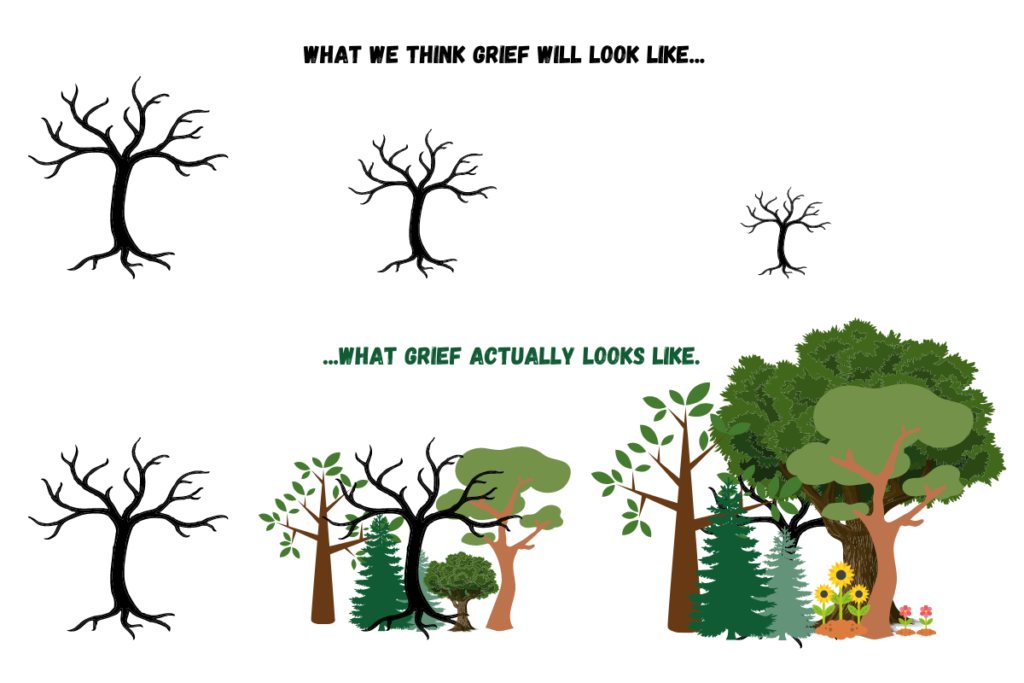

If you do encounter someone grieving, consider sharing the visual below. Grief doesn’t go away. Life gets built around it.

Final Thoughts – My Question for You

There are many emotions entangled in death and money.

End of life care is not great. Most people have a more complex life than they need and would benefit from simplicity and consolidation.

Actively set boundaries and stick with them.

If you have a terminal illness, consider a prepaid burial arrangement to make it easy on your family.

Hiring professionals, such as attorneys, accountants, and financial planners can help remove some of the heavy lifting you need to do.

It’s not easy to “wrap up” someone’s life. There is paperwork, decisions to be made, debts to be paid off, and money to be distributed.

Grief is unique and inheritances can be strange. It’s messy, and you are doing your best.

I’ll leave you with one question to act on.

What lessons have you learned about death and money?