Are your beneficiaries correct?

Are you sure?

Because beneficiary mistakes can be one of the most costly and heartbreaking mistakes in financial planning.

Plus, they are easy to make.

Someone gets married or divorced and forgets to update a retirement account beneficiary. An account is opened quickly naming one child as the beneficiary, but they forget to update it later to all their children. A beneficiary is named in conflict with a Will or Trust.

Or, no beneficiary is named because they think they are covered by their Will, failing to account for the tax consequences and administrative burden of not naming a primary beneficiary. Alternatively, someone adds a transfer on death designation to an investment account that is in conflict with their Will, causing one beneficiary to receive far more of an inheritance.

Beneficiary mistakes happen. They can cause incredible family issues – emotionally and financially.

Let’s talk about how and when to review your beneficiaries, how to coordinate your beneficiaries with your estate plan, the difference between primary and contingent beneficiaries, the difference between per stirpes and per capita beneficiary designations, who is generally not a good idea to name as a beneficiary, and the advantages and disadvantages of naming a trust as a beneficiary.

Review Your Beneficiaries

The first step in deciding if your beneficiaries are correct is to review them – all of them.

I emphasize all of them because it’s easy to forget accounts opened twenty years ago, an old 401(k) you didn’t know you had, or a small bank account you don’t use regularly. These can lead to beneficiary mistakes.

How to Review Your Beneficiaries to Avoid Beneficiary Mistakes

Identify all your accounts and ask the custodian for your latest beneficiary form. In today’s digital world, I still prefer asking for a copy of your latest beneficiary form.

Many custodians list your beneficiaries online, but I’ve seen mistakes where what was listed online does not match the actual signed beneficiary form. In the case of death, the custodian is likely going to use the signed form – not what is listed online. The form is the legally binding document – not the online information.

After you have a copy of the beneficiary form, does everything look correct?

Is everybody listed by name and not “all my children”? If someone died, were they removed and a new form submitted? If someone had children, are those children included?

Reviewing your beneficiaries is the first step in avoiding costly beneficiary mistakes.

When to Review Your Beneficiaries to Avoid Beneficiary Mistakes

I’m amazed by how frequently life or tax laws can change.

I generally suggest reviewing beneficiaries every few years or any time a major life event occurs, such as marriage, divorce, birth of a child, death, etc.

These events are good times to add or remove beneficiaries as needed. If you think no major life event has occurred that warrants updating your beneficiaries, reviewing them every few years will hopefully help you catch any life events you may have missed.

Another good time to review beneficiaries is when any major legislation is passed that could impact estate planning or tax laws. Although a long time can pass between major legislation, there are times when major legislation occurs every couple of years, impacting plans that have been in place for decades.

In 2019, the Secure Act was passed, which changed how beneficiaries could take distributions from inherited retirement accounts. It was a major piece of legislation where it would have been wise to review your beneficiaries and estate plan to make sure your beneficiaries were accurate.

Reviewing your beneficiaries regularly should help avoid common beneficiary mistakes.

Do Your Beneficiaries Follow Your Estate Plan?

It’s really important to understand that naming a beneficiary trumps your estate plan.

An IRA beneficiary, transfer on death (TOD) designation, or payable on death (POD) designation, overrides anything said in your Will.

For example, if your Will says everything you own will go to your daughter Sue when you die, but you put your son Adam as the 100% primary beneficiary on your retirement accounts and put a payable on death designation on your bank accounts naming Adam, he will receive your accounts when you die – not Sue.

This is a very common mistake.

People either think their Will can take care of everything and don’t put beneficiaries or they put beneficiaries on accounts that conflict with what their Will says.

Your beneficiaries need to be coordinated with your estate plan.

One of the first things I suggest people do is to review what their attorney suggested for beneficiaries when they completed their Will. Often, the attorney provides a cover letter that is one or two pages that says to update beneficiaries with certain language. It’s not an actual part of the Will, but a supplemental write up prepared by the attorney.

One of the most common beneficiary mistakes I see is people adding payable on death or transfer on death designations to investment or bank accounts to avoid probate, but then that beneficiary designation overrides a key planning strategy inside the Will.

There are times where it makes sense to add a POD or TOD designation to investment or bank accounts, but it should be something that is discussed with an estate planning attorney to make sure it is the best strategy.

To help avoid beneficiary mistakes, understand why your beneficiaries are listed on each account and how that coordinates with your Will.

Primary Beneficiary vs. Contingent Beneficiary – Understanding the Differences

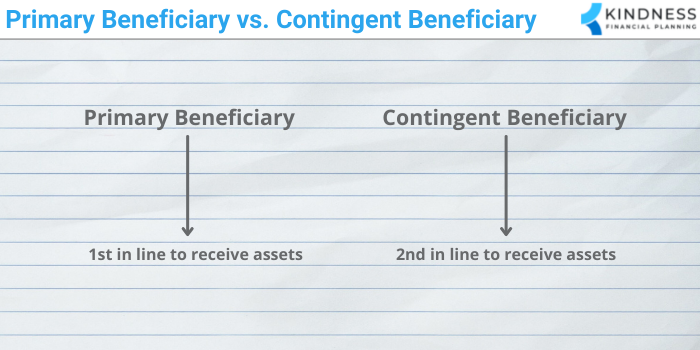

First, let’s define primary beneficiary and contingent beneficiary because it will then help you understand the difference between per stirpes and per capita.

These are important terms to understand because the order in which people die and how you list beneficiaries can have a profound impact on who receives what.

Primary Beneficiary Meaning

The primary beneficiary is the person(s) or organization(s) who receive assets first. If you die, the primary beneficiary is first in line to receive them.

Contingent Beneficiary Meaning

The contingent beneficiary is the person(s) or organization(s) who is next in line to receive assets if no primary beneficiaries are still alive.

How Primary Beneficiaries and Contingent Beneficiaries Work in Practice

Let’s say you name your three children, Neil, Sarah, Jasmine, as each one third primary beneficiaries.

You also name your two grandkids, Elena and Simon, as 50% contingent beneficiaries. Simon and Elena are Sarah’s kids. Neil and Jasmine don’t have kids.

All Three Kids Alive

If you die today while Neil, Sarah, and Jasmine are alive, they each get one third of the account. Simon and Elena, the grandkids, receive nothing.

One Kid Deceased

In this scenario, Sarah passes away, but Neil and Jasmine are still alive. Neil and Jasmine will each receive 50% of the account. Sarah receives nothing because she is deceased, and her two kids also receive nothing because her remaining share goes to the other primary beneficiaries.

Elena and Simon, as contingent beneficiaries, only receive money if all the primary beneficiaries die before them.

Two Kids Deceased

If Sarah and Neil both pass away, but Jasmine is living, she will receive 100% of the account.

Three Kids Deceased

Since all three kids are deceased and Elena and Simon, the grandkids, are still living, they split the account 50/50.

Since nobody knows when they will pass away, it’s vital to understand who receives what under different scenarios. Let’s talk about per stirpes and per capita beneficiary designations to build on your understanding.

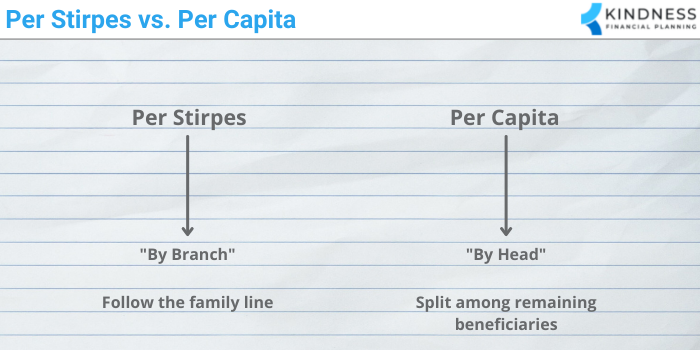

Per Stirpes vs. Per Capita – Understanding the Differences

I’m going to define per stirpes and per capita first and then follow up with an example to make it more clear.

Per Stirpes Meaning

Per stirpes is a latin term meaning “by branch.”

You can think of per stirpes as following your family’s line, or lineal descendants, if a beneficiary dies before the original owner.

Per Capita Meaning

Per capita is a latin term meaning “by head.”

You can think of per capita as the inheritance being split among the remaining beneficiaries if a beneficiary dies before the original owner.

How Per Stirpes and Per Capita Beneficiary Designations Work in Practice

I know per stirpes and per capita are difficult to understand without an example. Let’s look at an example to make sense of them.

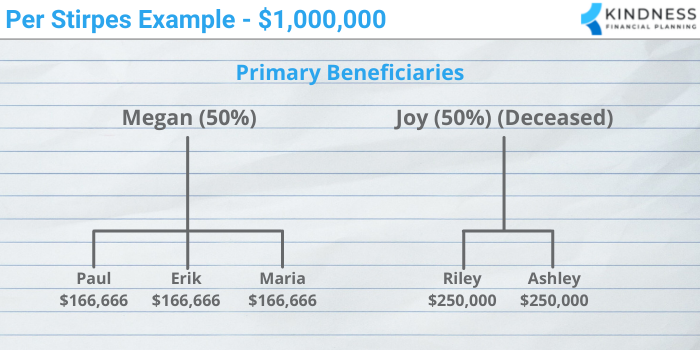

Per Stirpes

Let’s introduce a new family with two kids, Megan and Joy. Megan has three kids: Paul, Erik, and Maria. Joy has two kids: Riley and Ashley.

Let’s look at a per stirpes example with percentages and dollar figures to make it easier to track.

In this example, Megan and Joy are each named 50% primary beneficiaries of a $1,000,000 account.

Now, let’s say Joy passes away before you. After you pass away, and assuming everyone else is still living, Megan gets her half, or $500,000. Riley and Ashley split what would have been Joy’s half. Riley and Ashley each get one fourth, or $250,000.

Remember, per stirpes follows the family line, which is why Riley and Ashley split Joy’s portion.

If Megan and Joy had both passed away before you, Riley and Ashley would have received the same amount ($250,000) because they still share in Joy’s 50% share; however, Paul, Erik, and Maria would have each received approximately 16.67%, or approximately $166,666.

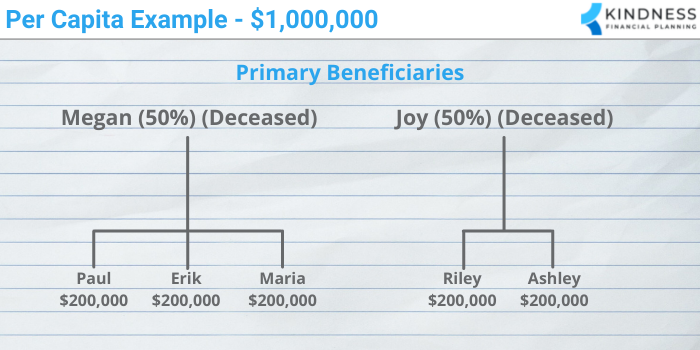

Per Capita

Continuing with the same people, let’s look at how per capita would change the distributions.

In this scenario, Megan and Joy both pass away before you, leaving the five grandkids to receive distributions.

Instead of Riley and Ashley getting 25% each and Paul, Erik, and Maria each receiving approximately 16.67%, each grandkid would receive 20%, or $200,000.

Since you selected per capita, the kid’s shares don’t follow down the lineal line, but instead, are split by the heads remaining. In this case, five grandkids remain, which means they split the 100%, which is why they each receive 20% of the $1,000,000.

Choosing a per stirpes or per capita beneficiary designation is a complicated process. The order in which people die and what you select presents many different scenarios in how much someone could receive. It’s really important to consult with an estate planning attorney to make sure that if you select per stirpes or per capita, the distributions will happen as you intend.

Who To Generally Not Name as Beneficiaries

Although I am not a fan of general rules when it comes to financial planning, there are a few beneficiaries most people generally do not name for good reasons. There are always exceptions, which is why you should talk with your own professional experts.

Minor Beneficiary

Naming a minor as a beneficiary is usually not a good idea for two reasons:

- Minors can’t receive money

- Most inheritances are turned over to them at the age of majority (often age 18 or 21)

Since minors are by definition not adults, money can’t actually be released directly to them.

It’s normally released to a custodian for the benefit of the minor. If your Will or beneficiary form does not specify a custodian, a court has to appoint a guardian, which can be expensive and time consuming.

On top of that, if a minor is named, they receive funds at the age of majority. Most people are not comfortable handing over a large sum of money to an 18 or 21 year old. Imagine if you died with $1,000,000 and your child received it at age 18. Would they use it responsibly?

There are young adults who could handle money responsibly at age 18 or 21, but I find most people would feel better if they received funds later in their 20s or 30s.

Generally, a trust is a better way to handle inheritances for minors because you can name who is the trustee of the trust and when distributions can occur. I’ll talk about this more in a later section.

Disabled Beneficiary

Disabled individuals usually are not a good choice to name as a beneficiary because if they are qualifying for government assistance or may in the future, an outright inheritance may disqualify them from government assistance.

Usually, people in this circumstance will set up a special needs trust to allow a disabled person to still benefit from the trust while qualifying for government benefits.

Special needs trusts can also help minimize the chance that a disabled person is taken advantage of by other people. Financial abuse is not uncommon.

If you think a special needs trust may help, it’s important to work with an estate planning attorney and possibly a financial planner who specializes in that area.

Estate as Beneficiary

Naming your estate as the beneficiary of an account is usually not preferable because then the assets go through probate. Depending on your state, this could be an expensive and time consuming process.

I’m originally from Washington, and probate there is a fairly inexpensive and short process compared to that of many other states. In contrast, California attorneys can charge a percentage of the estate value, which can be very expensive.

For example, probate might cost a few thousand dollars, usually billed based on an hourly rate, in Washington state for a $1,000,000 estate.

In California, it might cost $23,000 (4% on the first $100,000, 3% on the next $100,000 and 2% on the next $800,000).

This is why if you ever meet someone from California, they almost always try to put every asset they can into a trust to avoid probate.

Naming a beneficiary avoids probate, which means assets can usually be distributed faster and with less in fees.

Naming a Trust as a Beneficiary

Naming a trust as a beneficiary can be a smart strategy, but it must be done properly and regularly reviewed to make sure what was intended in the original planning still applies as laws change.

I told you earlier how having a trust for a minor beneficiary is helpful, but it can also be helpful for adults who struggle with money.

Since you can customize your trust, you can control when distributions are made, how much can be distributed, and who controls the trust to make the distributions. For people with family members prone to gambling, substance abuse, or other money problems, a trust can help prevent access to the money outright and spending it in harmful ways.

A trust can also be helpful to protect financial assets from creditors and divorce. For example, if you had a child or grandchild who is in a career where they are more likely to be sued, you may want to consider an irrevocable trust to add another layer of protection.

The downside of naming a trust as a beneficiary is that taxes can be higher because trusts are taxed at different rates than individuals. The tax rates tend to be higher at much lower levels of income. Plus, you may have to file a trust tax return in addition to your personal income tax return. It’s another layer of complexity, administration, and potentially fees.

Also, if you are naming a trust as the beneficiary of an IRA, there are very specific requirements to follow to make it a “see-through” trust, which can provide more favorable distribution rules.

Naming a trust as a beneficiary allows for more control, but it also can come with less favorable tax consequences and a higher administrative burden. Each individual should talk with a knowledgeable estate planning attorney to decide if naming a trust as a beneficiary makes sense.

Final Thoughts – My Question for You

You can make the best investment and financial planning decisions in the world, but if you don’t get your beneficiaries right, all that planning could be thrown out the window.

Most people want to control who receives their money when they die, and beneficiary forms are one method of making sure that happens.

It’s important to review your beneficiaries regularly, at least every few years or as major life changes happen.

Ask your custodian or financial institution for your latest beneficiary forms, and make sure you have them for all accounts! You don’t want to miss an account.

From there, understand who is named and the various scenarios of who could receive what depending on who passes away first. Make sure the beneficiary form works in coordination with your estate plan.

You don’t want your beneficiary form overriding important planning in your Will, and you also don’t want your Will doing the heavy lifting if a beneficiary form is a better method to distribute assets.

If you are tempted to name a minor, disabled individual, or your estate as a beneficiary, think twice. It’s generally not advisable, which is why it’s important to talk with an estate planning attorney.

Naming a trust as a beneficiary can help provide control, but it does come with worse tax consequences and more recordkeeping. You’ll need to weigh the pros and cons of naming a trust as a beneficiary.

I’ll leave you with one question to act on.

When will you review all your beneficiaries?