Last Updated on June 17, 2025

Capital gains vs. ordinary income – do you know the difference in how they are taxed?

If you are like many people, you may be wondering if recognizing capital gains can affect your ordinary income taxes or vice versa. Perhaps you’ve heard the phrase “long-term capital gains are stacked on top of ordinary income”, but aren’t sure what it means.

Maybe you want to recognize capital gains or do a Roth conversion as a new widow because it’s the last time you will file your taxes married filing jointly. Or, maybe you have a stock with a low cost basis that you want to sell, but are unsure of the tax consequences.

Regardless of your situation, understanding how capital gains and ordinary income taxes affect each other are important because then you can take advantage of tax planning opportunities to reduce taxes.

Let’s look at how ordinary income is taxed, how capital gains are taxed, and tax planning opportunities to use the tax code to your advantage.

How is Ordinary Income Taxed?

First, let’s look at how ordinary income is taxed and then build on your knowledge with understanding how short-term and long-term capital gains are taxed.

What’s Included in Ordinary Income for Taxes?

Ordinary income is income you earn through wages, commissions, interest from bank accounts, interest from bonds, income from a business, rents, royalties, nonqualified dividends, and short-term capital gains.

It’s important to note that ordinary income does include short-term capital gains, which occur when you sell an investment for a profit that you’ve held less than a year.

For example, if you earned $250,000 from wages, $3,000 of interest from bank accounts, $15,000 of interest from bond ETFs in a brokerage account, $30,000 from net rental income, and $10,000 in short-term capital gains in 2025, your total ordinary income would be $308,000.

Let’s look at the ordinary income tax brackets to see how that would be taxed.

Ordinary Income Tax Brackets

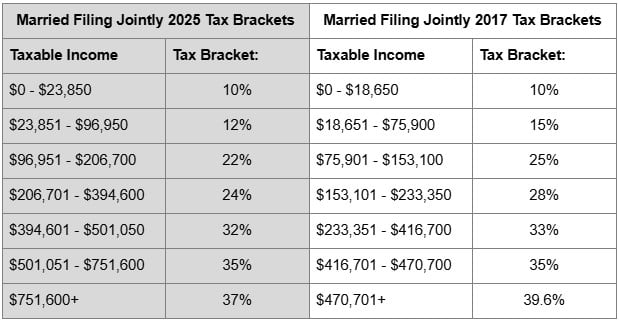

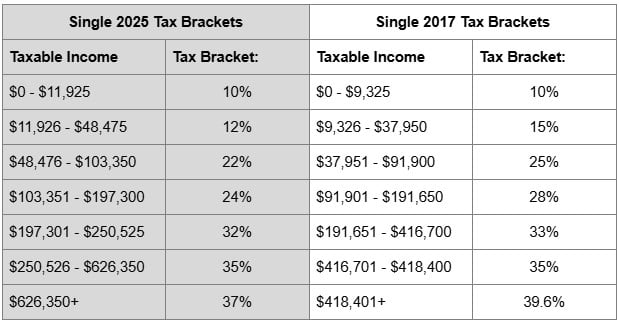

The first piece of knowledge you should know is that the tax rates passed under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in 2017 are temporary. If no action is taken before 2026, these tax rates will expire at the end of 2025. In 2026, we will go back to the 2017 tax rates adjusted for inflation.

The tax rates we have today are lower and much wider, meaning generally, more income is taxed at lower rates when compared to 2017.

In other words, given the same level of income, most people will find themselves paying more in taxes in 2026 than in 2025.

Below are the tax brackets in 2025 and 2017.

As you can see, many people who are in the 22% tax bracket today may find themselves in the 25% or 28% tax bracket in 2026 and people in the 24% tax bracket today may find themselves in the 28% or 33% tax bracket in 2026, assuming similar levels of income.

I mention this because there are tax planning strategies around this I’ll talk about later in this article; however, for now, let’s look at how to calculate your ordinary income taxes.

How to Calculate Your Ordinary Income Tax

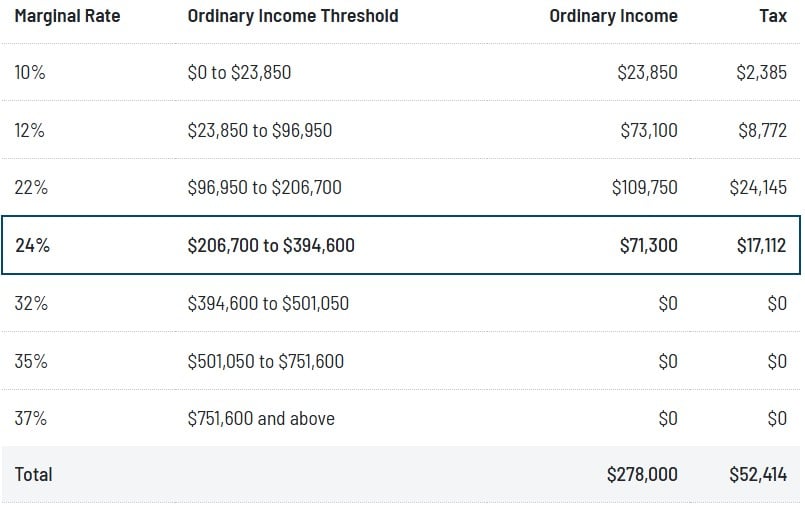

Continuing the example from above, let’s assume you have $308,000 of ordinary income. Let’s assume you have no other income, which means the $308,000 is also your gross income. Let’s also assume there are no adjustments to your income, such as certain business expenses, student loan interest, or educator expenses, and that the $308,000 is also your adjusted gross income (AGI).

Next, let’s assume you are under age 65 and take the standard deduction for a couple married filing jointly, which is $30,000 in 2025.

That brings your taxable income to $278,000.

A taxable income of $278,000 puts you in the 24% tax bracket, but that doesn’t mean the full $308,000 is taxed at 24%.

The tax brackets are progressive, meaning that you fill up each bracket first before each additional dollar is taxed at the higher rate.

For example, the first $23,850 is taxed at 10%, the income between $23,851 and $96,950 is taxed at 12%, between $96,951 and $206,700 is taxed at 22%, and $71,300 is taxed at 24%.

The estimated total federal tax is $52,414. If you divide that by the taxable income of $278,000, that is an effective tax rate of approximately 19%.

Now that you understand how ordinary income taxes are calculated, let’s switch gears to how capital gains are taxed.

How Are Capital Gains Taxed?

Long-term capital gains have a special carve out within the tax code and receive preferential tax treatment.

Short-Term vs. Long-Term Capital Gains

As I mentioned earlier, short-term capital gains occur when investments held less than a year are sold for a profit. They are taxed as ordinary income.

Long-term capital gains occur when an investment is sold for a profit that is held more than a year.

They are taxed at their own special long-term capital gains bracket – not the ordinary income tax brackets.

Long-Term Capital Gains Brackets – 0%, 15%, and 20%

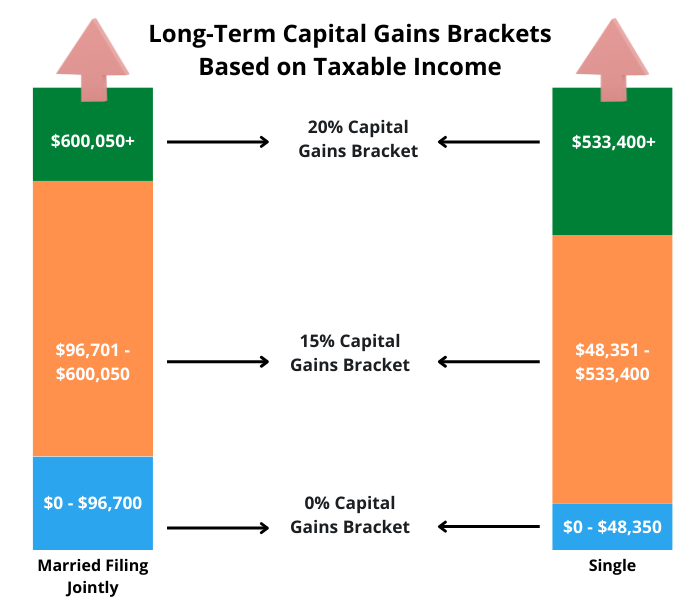

There are three long-term capital gains brackets: 0%, 15%, and 20%.

Yes, you read that correctly. You can recognize long-term capital gains and pay zero tax on them. This is the 0% long-term capital gains bracket strategy. I talk about this more in the tax planning strategies at the end.

Depending on your income, you could be in the 0%, 15% or 20% long-term capital gains brackets.

As you can see, long-term capital gains taxes are generally lower than ordinary income tax brackets.

When you file taxes married filing jointly, you pay zero long-term capital gains taxes on taxable income up to $96,700. For capital gains above that amount up to $600,050, you only pay 15%. If you compare that to ordinary income taxes, it’s a bargain!

Let’s look at exceptions to long-term capital gains brackets and then understand if long-term capital gains can push you into a higher tax bracket.

Exceptions to Long-Term Capital Gains Brackets

There are exceptions to the long-term capital gains brackets.

For example, if you sell a primary residence and qualify for the home sale exclusion, you can exclude $250,000 of the capital gain if single or $500,000 if you file a joint return with your spouse.

Collectibles are also an exception. Collectibles, such as antiques, fine art, and coins are usually taxed at 28%.

If you have rental property, there is usually depreciation recapture when you sell it. The tax rate on depreciation recapture is 25%.

Otherwise, investments in a brokerage account and many other investments held for more than a year will be taxed at the 0%, 15%, or 20% long-term capital gains brackets.

Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT)

Another tax to be aware of with capital gains and ordinary income is the net investment income tax.

Net investment income includes capital gains (short-term and long-term), dividends (qualified and nonqualified), taxable interest, rental income, royalty income, and a few other sources of income that are less common.

It’s a 3.8% surtax, or additional tax, on the lesser of your net investment income or excess of modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) over $250,000 if married filing jointly or $200,000 if single.

Example 1 – Net Investment Income is Less Than MAGI Overage

If you file married filing jointly, your MAGI is $300,000, and your net investment income is $40,000, you are over the MAGI of $250,000 by $50,000.

Since the $40,000 net investment income is less than the MAGI overage, you’ll owe the 3.8% net investment income tax on $40,000 – not the $50,000 overage.

Your additional net investment income tax would be $1,520 (3.8% x $40,000).

Example 2 – MAGI Overage is Less Than Net Investment Income

If you file married filing jointly, your MAGI is $270,000, and your net investment income is $40,000, you are over the MAGI of $250,000 by $20,000.

Since the $20,000 MAGI overage is less than the $40,000 net investment income, you’ll owe the 3.8% net investment income tax on $20,000 – not the $40,000 net investment income.

Your additional net investment income tax would be $760 (3.8% x $20,000).

Can Long-Term Capital Gains Push Me Into a Higher Ordinary Income Tax Bracket?

You may have heard the phrase “long-term capital gains get stacked on top of ordinary income.”

Does that mean long-term capital gains can push you into a higher tax bracket?

No, long-term capital gains will not push you into a higher ordinary income tax bracket.

Since long-term capital gains get stacked on top of ordinary income, recognizing long-term capital gains will not cause your ordinary income taxes to go up; however, your ordinary income can affect your long-term capital gains tax bracket.

In other words, ordinary income affects long-term capital gains tax brackets. Long-term capital gains do not affect ordinary income tax brackets.

It’s a one way street because ordinary income is taxed first – then long-term capital gains are taxed.

However, recognizing long-term capital gains does increase your adjusted gross income (AGI), which can cause more of your Social Security benefits to be taxable, phase out itemized deductions and some tax credits, and push you above the phaseout levels to make Roth IRA contributions or deductible IRA contributions.

If you need a good way to remember this information, you can watch this video where I include a fun science experiment.

How to Calculate Your Long-Term Capital Gains Tax

Let’s look at an example to make it clearer that capital gains won’t push you into a higher ordinary income tax bracket.

I’m going to use a simple example, but if you want to use a calculator to estimate your capital gains tax, SmartAsset has a good capital gains calculator.

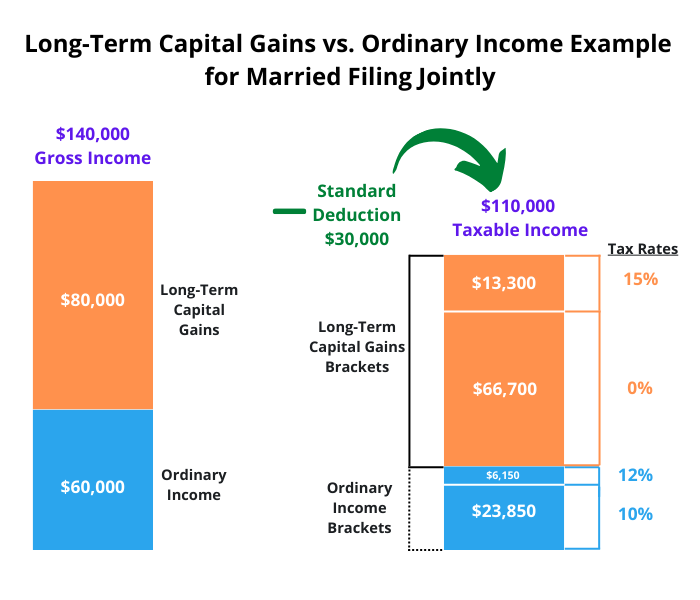

Let’s say you file as married filing jointly with a gross income of $140,000, which is composed of $60,000 in ordinary income and $80,000 of long-term capital gains. After the standard deduction of $30,000, your taxable income is $110,000.

That will put you in the 15% capital gains bracket, but a few interesting things to note:

- You are in the 12% ordinary income tax bracket.

- Part of your long-term capital gains are taxed at 0%

- Part of your long-term capital gains are taxed at 15%.

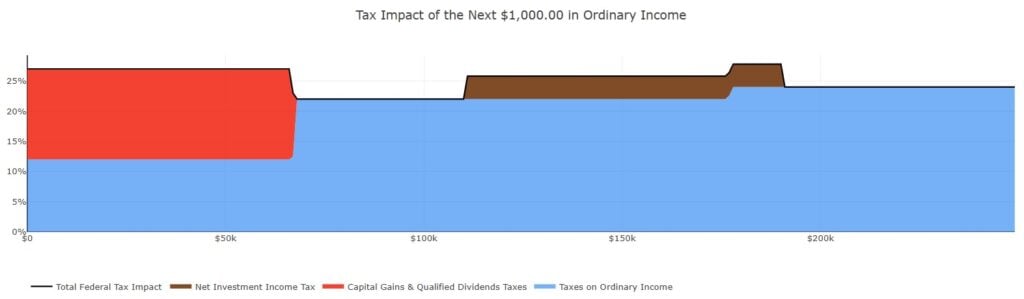

- The effective tax on the next $66,000 of ordinary income is about 27% (red in the chart below) because it drives up the long-term capital gains taxes.

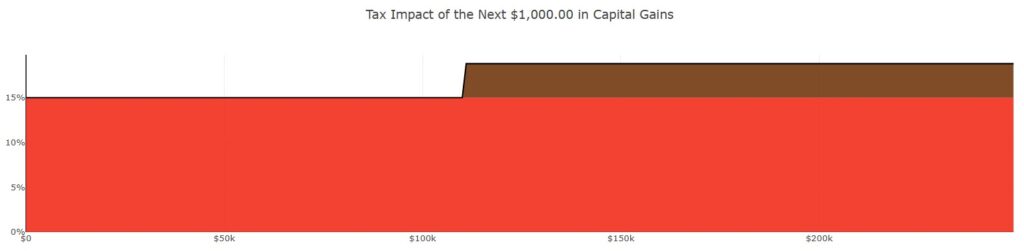

As you can see in the chart below, recognizing long-term capital gains does not change taxes on ordinary income – only the capital gains.

What’s happening in this example?

Below is a visual of what happens.

The first $60,000 of ordinary income is taxed first. Then, the long-term capital gains are taxed at their own rate.

If you subtract the standard deduction of $30,000 from the $60,000 of ordinary income, that leaves you with $30,000 of taxable income.

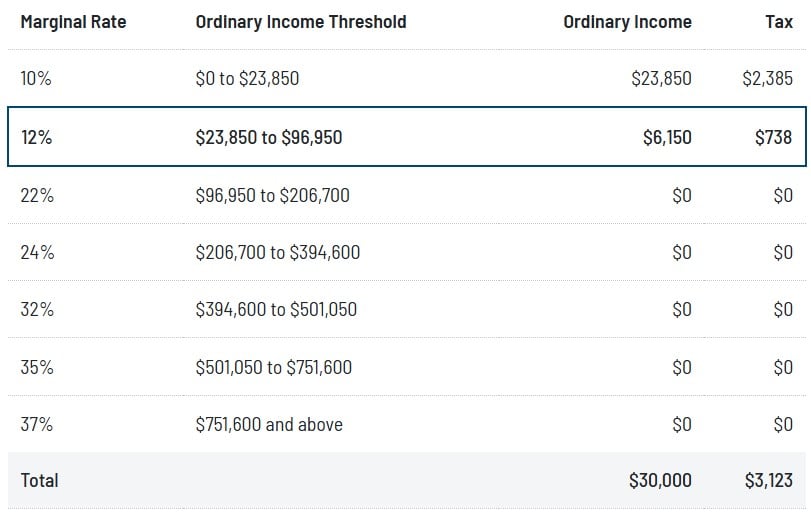

The first $23,850 of ordinary income is taxed at 10% or $2,385 total. The next $6,150 of ordinary income is taxed at 12%, or $738. Combined, you are paying about $3,123 in ordinary income taxes.

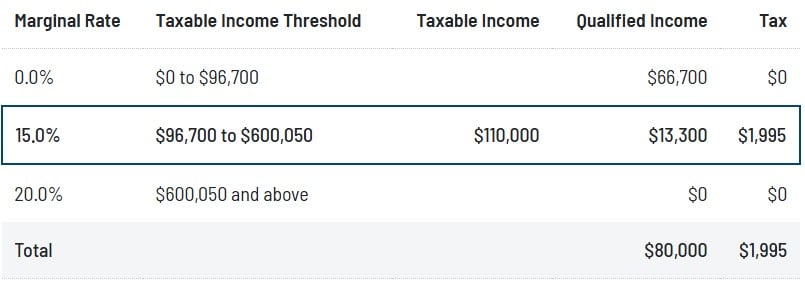

Since your taxable income is $110,000, that puts you in the 15% long-term capital gains bracket.

The first $66,700 of long-term capital gains ($96,700 upper limit on 0% capital gains minus $30,000 taxable income) are in the 0% long-term capital gains bracket. In other words, there is zero tax on the first $66,700 in long-term capital gains. The next $13,300 are taxed at the 15% long-term capital gains bracket, which is $1,995 in long-term capital gains taxes.

In total, you are paying $3,123 in ordinary income taxes and $1,995 in long-term capital gains taxes for a total of $5,118.

Your effective tax rate is about 4.7% ($5,118 in taxes divided by $110,000 in taxable income).

Despite being in the 12% marginal tax bracket and the 15% long-term capital gains bracket, your effective rate was less than 5% because a large portion of the income was from long-term capital gains and a large portion of the long-term capital gains were taxed at 0%!

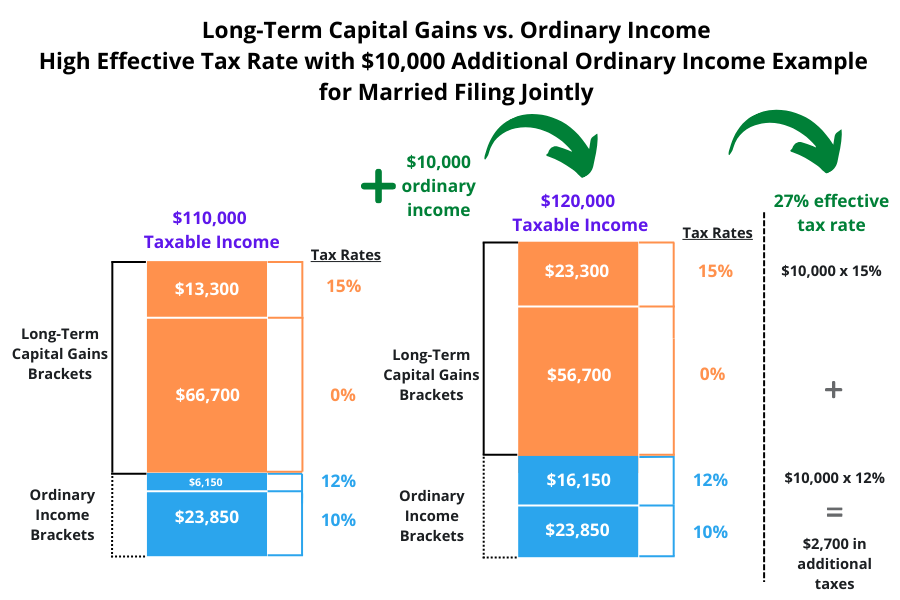

Now you may still be wondering why the effective tax rate on the next $66,000 of ordinary income is 27%. The reason for this is because each additional dollar of ordinary income up to $66,000 is taxed at a 12% ordinary income tax rate, but it also makes the income that was being taxed at 0% now taxed at 15%. Adding those together, you get a 27% effective tax rate.

Below is a visual of what happens.

This is what I meant earlier by the fact that ordinary income can push you into a higher capital gains bracket, but capital gains won’t push you into a higher ordinary income tax bracket.

The additional ordinary income is pushing capital gains out of the 0% long-term capital gains tax bracket into the 15% tax bracket. For example, if you had $10,000 of additional ordinary income, you would pay an additional 12% of ordinary income taxes and it would push the $66,700 of long-term capital gains taxed at 0% to $56,700. Then, the $10,000 of long-term capital gains that used to be taxed at 0% would be taxed at the 15% long-term capital gains tax bracket.

Doing the math, that works out to $1,200 in ordinary income taxes ($10,000 x 12%) and $1,500 in long-term capital gains taxes ($10,000 x 15%). Together, that is $2,700 in additional taxes or a 27% effective tax rate ($2,700 divided by $10,000 of additional ordinary income).

Tax Planning Strategies

Now that you know more about how ordinary income and capital gains are taxed, let’s look at the proactive tax planning strategies you can use to leverage the tax code for your benefit.

Reduce Your Lifetime Taxes with Roth Conversions

I’ve previously written about the benefit of Roth conversions, which means I won’t go into the same level of detail here, but I do want to show you how to think about Roth conversions and long-term capital gains in retirement.

First, a Roth conversion is where you move money from an IRA to a Roth IRA, pay taxes on it today, and the money in the Roth IRA can grow tax-free.

A Roth conversion is typically beneficial if your tax rate in the future will be higher than it is today. Since the tax rates are lower and wider today, there are many people who would benefit from a Roth conversion. As I mentioned earlier, many people in the 22% tax bracket may find themselves in the 25% or 28% tax bracket in 2026. For people in the 24% tax bracket today, they may find themselves in the 28% or 33% tax bracket later. Which rate would you rather pay?

I know I’d rather pay the lower rate today.

Another consideration is whether you plan to need your Required Minimum Distribution (RMD) in retirement. For example, if your RMD is $80,000 in the future, but you only need $40,000 to supplement your other income, it may make sense to do a Roth conversion because it will reduce your RMD. Plus, money in the Roth can grow tax-free, be distributed tax-free, and heirs can distribute money tax-free.

If you become a widow this year, it’s your last year to file married filing jointly. This may present an opportunity to do a Roth conversion and pay less tax compared to next year.

Many people who retire early or take a sabbatical leave can often benefit from doing a Roth conversion in lower income years to reduce the tax they will have to pay later, but it’s important to understand how a Roth conversion can affect your capital gains tax.

Using the 0% Long-Term Capital Gains Bracket to Pay Zero Tax

To illustrate a simple example, let’s assume you are married and file jointly, you recently retired, and have no other income. You’ll likely have interest from a bank account or dividends from a brokerage account, but let’s ignore that for a moment to make the numbers easier to track.

Let’s say you need $150,000 annually for living expenses.

Since you haven’t started Social Security yet because you want to optimize your benefits, you need to create cash in your brokerage account, which would cause $130,000 in capital gains. You are selling very low cost basis stock you’ve held for a long time.

If you left it at that for the year, your total income would be $130,000 and your taxable income would be $100,000.

Since the first $96,700 of long-term capital gains are taxed at 0%, your tax bill will be very low. You will pay about $495 of tax ($3,300 of long-term capital gains taxed at 15%).

Another alternative is to not use the 0% long-term capital gains bracket and do a Roth conversion instead.

For example, you could decide to trade the $126,700 of long-term capital gains taxed at 0% for a Roth conversion of $126,950 that is taxed at 10% and 12%. The reason the numbers are slightly off ($126,700 for capital gains vs. $126,950 for ordinary income) is because the ordinary income tax bracket for 12% doesn’t match up perfectly with the 0% long-term capital gains tax bracket.

If you decide to do a Roth conversion and recognize the long-term capital gains, remember that ordinary income is taxed first and long-term capital gains are stacked on top.

In that scenario, you could convert $126,950 in the 10% and 12% tax brackets, which would be a total tax of $11,157.

Then, the capital gains would be stacked on top and taxed at 15%.

What you are doing is giving up the 0% long-term capital gains rate on $126,700 of long-term capital gains to pay 10% or 12% on the Roth conversion, which can grow tax-free for your life and part of your heirs’ lives. Given where tax rates may be in the future, not only with them changing back to higher rates in 2026, but potentially later in life, a Roth conversion may help reduce taxes over your lifetime.

If you don’t want to give up the 0% long-term capital gains bracket, you could alternate years. For example, in 2025, you could focus on the 0% long-term capital gains bracket, create enough cash for this year and next, and not do a Roth conversion. Then, in 2026, you could do a Roth conversion and minimize long-term capital gains. In 2027, you could flip back to creating long-term capital gains and not doing a Roth conversion. This is one method of doing a Roth conversion and hedging tax rates while still taking advantage of the 0% long-term capital gains bracket.

The ideal strategy is going to depend on your income, future income, and tax rates, which is why it’s important to do an analysis at least annually.

Reduce Your Taxes with Donor-Advised Funds

This is a strategy for people who are already charitably inclined. If you don’t already give to charity, this strategy doesn’t make sense for you.

Another strategy to consider is higher amounts of charitable giving in coordination with a Roth conversion. For many people, bunching many years’ worth of gifts into a single year and contributing it to a donor-advised fund is an ideal strategy.

Depending on your other income and other itemized deductions (read the linked article for an in-depth guide about how to use it), you may be able to get the tax benefit of a charitable deduction today, but can control the timing and amount of the grants that go to the charities you select.

If you are planning to contribute money to a donor-advised fund and want to coordinate with the 0% capital gains bracket and Roth conversions, it’s typically best to make a donor-advised fund contribution in the year you do the Roth conversion – not when you are recognizing capital gains.

The reason for this is because a charitable contribution is going to be more valuable when it offsets ordinary income.

If you do a Roth conversion to fill up the 24% tax bracket, the charitable contribution is going to offset that income first. For example, if you contribute $10,000 to charity, that may offset $10,000 of income, effectively saving you about $2,400 in taxes. Instead of taking the tax savings, you could decide to convert $10,000 additional dollars in the 24% tax bracket.

Making a donor-advised fund contribution may allow you to convert approximately the same amount to a Roth conversion as the contribution and stay within the same tax bracket.

For instance, if you contribute $20,000 to a donor-advised fund, that may allow you to convert $20,000 additional dollars, but pay no more in taxes. It’s not exactly a dollar-for-dollar benefit, but an approximation.

If you compare that to making donor-advised fund contributions in the year you are recognizing capital gains, the charitable contribution is only going to save you taxes at a rate of 15%.

For example, if you are already at the top of the 0% capital gains bracket, recognizing additional capital gains will be taxed at 15%. A donor-advised fund contribution may allow you to offset the additional capital gains to bring it back to the 0% capital gains bracket.

If we assume you contributed the same $10,000 as before to charity, but in a year where you are focusing on long-term capital gains only, the $10,000 contribution is going to save you approximately $1,500 in taxes. This is less than the $2,400 in savings when you are doing Roth conversions to the top of the 24% tax bracket.

Since ordinary income rates tend to be higher than long-term capital gains rates, charitable contributions and bunching contributions into a donor-advised fund are more valuable to offset Roth conversions.

If you decide to do a Roth conversion and recognize long-term capital gains, the charitable deduction will offset the ordinary income that is taxed at a higher rate until it is fully used. Then, it will offset the lower long-term capital gains tax.

If you are charitably inclined, it’s vital to create a long-term charitable giving strategy that works in coordination with Roth conversions or recognizing long-term capital gains.

Final Thoughts – My Question for You

Our tax system is complex.

When it comes to ordinary income, it’s important to remember that tax rates are progressive, meaning if you make more, not every dollar is taxed at the higher rate – only the dollars within that bracket.

When it comes to long-term capital gains, it’s important to remember that there are three brackets – 0%, 15%, and 20%. Long-term capital gains are taxed at their own capital gains brackets and can be affected by ordinary income.

When it comes to ordinary income and long-term capital gains, long-term capital gains are normally taxed at a much more favorable tax rate. While ordinary income can increase the tax you pay on long-term capital gains, long-term capital gains can’t increase your ordinary income tax rate.

If you think about the water and oil example from the video, water (ordinary income) will always go to the bottom and long-term capital gains (oil) will always rise to the top. Ordinary income (water) is always taxed first.

Since your income can fluctuate year-to-year, it’s important to do a mock tax return projection each year. It can help you decide how much income to recognize and which tax planning strategies to use.

I’ll leave you with one question to act on.

Which strategies will you use this year to reduce the taxes you pay over your lifetime?