Last Updated on June 17, 2025

The stock market going down is a natural part of investing. When an investment goes down in value, there are silver linings.

One of the silver linings is that you may be able to use a strategy called tax-loss harvesting, where you sell an investment for a loss in a brokerage account.

The benefit of this strategy is that you may be able to use that loss to offset capital gains, ordinary income, and future capital gains while still having similar performance in the portfolio.

Let’s talk about what tax-loss harvesting is, the benefits, how to do it, risks, and an example of how tax-loss harvesting could be done.

What is Tax-Loss Harvesting?

Tax-loss harvesting is where you sell an investment that has gone down in value to “book” or “capture” a tax-loss. Ideally, you also buy a similar investment on the same day to maintain exposure to the same area of the market. I’ll talk about this in more detail in a later section.

The loss you booked can then be used to offset capital gains and potentially ordinary income.

Tax-loss harvesting is a strategy to reduce and defer taxes.

What are the Benefits of Tax-Loss Harvesting?

The benefits of tax-loss harvesting are that you can use losses to offset capital gains to reduce your tax burden. These benefits are only available inside of a brokerage account – not an IRA, Roth IRA, 401(k), 403(b), etc.

A big benefit of the losses is that they expire when you do. In other words, losses carry forward until you die.

There are three main benefits of tax-loss harvesting:

- Use losses to offset capital gains

- Any excess up to $3,000 can offset $3,000 of ordinary income

- Any additional excess above current year capital gains and $3,000 of ordinary income offset can be carried forward until you die to offset future capital gains and up to $3,000 of ordinary income each year

Tax-loss harvesting is not a permanent tax savings.

When you tax-loss harvest, you are lowering the cost basis of your investment, which means your future capital gains may be higher; however, if you want to defer taxes as long as possible, it can be a good strategy.

Also, if you never plan on spending the full amount of your portfolio, your brokerage account may receive a partial or full step up in cost basis at death. This means you could reduce taxes during your lifetime and then your heirs may be able to receive your assets at death with minimal tax consequences.

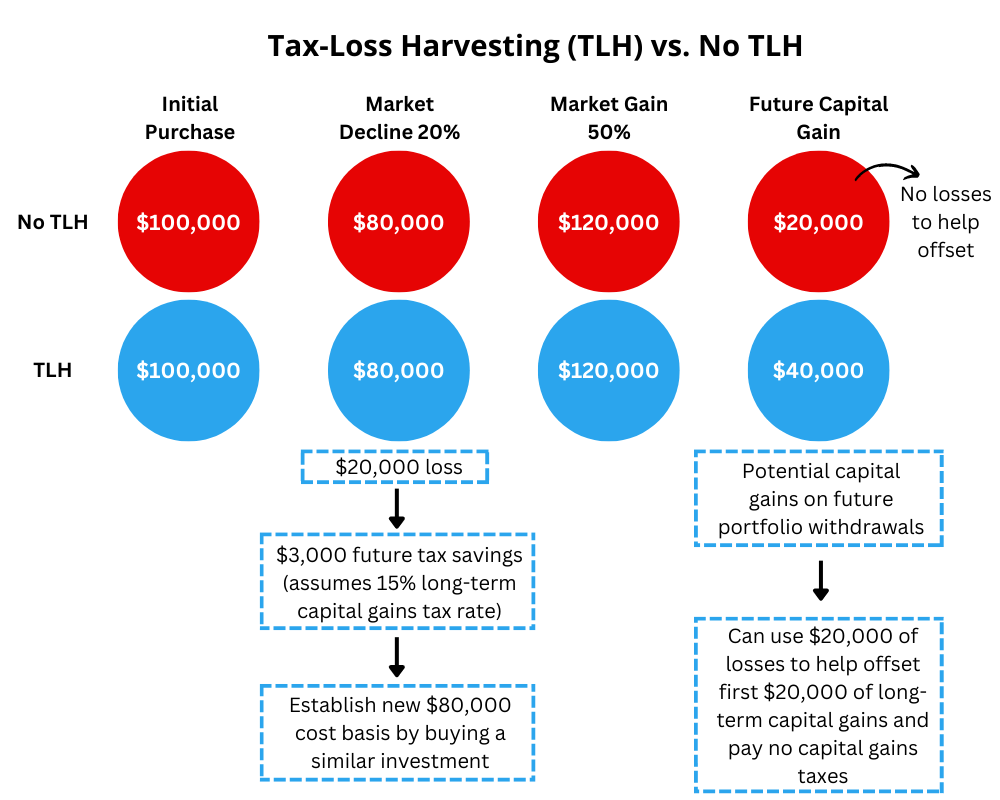

For example, if you have a $100,000 investment that goes down 20%, the current value would be $80,000. You could wait for it to recover, but if you do, you miss out on the opportunity to tax-loss harvest.

Let’s say you sell it at $80,000 and buy a similar investment worth about $80,000, which establishes a new cost basis of $80,000 instead of the original $100,000. You “booked” a $20,000 loss for tax purposes. The market then goes up 50% the following year. Your $80,000 investment becomes $120,000.

On paper, you show a $20,000 loss for tax purposes, but your investment is up $20,000 from where it originally started and $40,000 from the tax-loss harvest point.

If you were to sell it, you would have a $40,000 capital gain. If you had not tax-loss harvested, your original cost basis of $100,000 would apply, which means if you sold it, there would only be a $20,000 capital gain instead of $40,000.

That’s what I mean by the taxes are deferred – not a permanent savings.

In reality, most people are not selling entire positions a year later, which means they often can continue deferring those taxes for longer.

How to Do Tax-Loss Harvesting

Tax-loss harvesting can be an easy concept to understand, but the implementation of it can be challenging.

As with any tax strategy, you need to understand the rules and assume the IRS has already thought through any tricks you could play to try to get around the rules.

Look at Investments Year-Round – Not Only at Year-End

Many people tend to look at investments at scheduled points throughout the year, potentially only at the end or beginning of the year. Although it’s possible to identify tax-loss harvesting opportunities during those points in time, a better strategy would be to have an alert system that notifies you if an investment has gone down in value by a meaningful amount.

As a fee-only financial planner, I have software that screens my client portfolios and alerts me when there are tax-loss harvesting opportunities.

If you are only looking a few times a year, there is a good chance you will miss opportunities to see the portfolio down and trade the account. You want to capture the losses as they occur, which could be at any point.

Identify a Similar Investment – Wash Sale Rule

You can wait 31 days after the sale and buy the same fund you sold for a loss, but many people do not want to wait 31 days because that means you have money invested in cash instead of the stock market. Since high returns often come alongside low returns, it can be risky waiting in cash. If the stock market recovers, you may miss part of the upside.

Unless you want to wait 31 days after the sale and buy the same fund you sold for a loss, the next step to take is to identify the investments with losses and find similar, but not substantially identical investments.

What does substantially identical mean?

It depends who you ask. The IRS hasn’t clearly defined what makes investments substantially identical.

Many people would make the case that you can’t swap an ETF tracking the S&P 500 for a different ETF tracking the S&P 500 because they would be substantially identical. They might also say you can’t swap a mutual fund for the same ETF version. Someone might suggest going from an S&P 500 ETF to a Russell 1000 Index because they track a different index.

People reach different conclusions based on their own comfort level.

Ultimately, you need to be comfortable with the decision you could defend if you had to make the case before an IRS agent.

The problem with buying an investment that is substantially identical is that you could trigger the wash sale rule, which disallows the loss you attempted to book.

A wash sale occurs when you sell an investment for a loss and buy a substantially identical security within 30 days before or after the sale.

For example, if you bought 10 shares of ABC ETF for $1,000 on June 1, sold them on June 10 for $800, and bought them back on June 20, you would have a wash sale and the $200 tax loss would be disallowed. The cost basis would remain $1,000.

Pick the Specific Cost Basis Lot

Once you identify the investment with a loss and a similar, but not substantially identical investment, you may be able to specify which cost basis lot you want to sell.

This is important because you could have an investment with multiple lots – some trading at a gain while others trade at a loss. By picking the specific lot, you can sell only the ones with the losses and leave the ones with the gains. Or, if you want to keep your portfolio simple, you could sell the entire investment.

You’ll need to see which method of selling you have on your brokerage account. For example, you might be on the “average cost” method for mutual funds and unable to pick specific lots. If you are unsure, you can call your custodian and ask them if you can sell a specific lot.

If you can specify the lot, consider doing it.

Sell Investment at a Loss and Buy a Similar Investment

After that, you can sell the investment that has a loss and use the proceeds to buy a similar investment the same day. If it fits within your investment policy statement, you could also consider selling another investment that has held its value better and use those proceeds to add a little to your purchase.

This way you are rebalancing by selling something that has done well to buy something that may be underweight.

For example, if ABC Investment has a normal target weight of $100,000, and it’s at $80,000, you may consider selling about $20,000 of another investment that is currently above its target weight to be able to purchase $100,000 to get it back to target.

Avoid Wash Sales

After you do the tax-loss harvesting, you need to carefully trade for the next 30 days.

As I mentioned earlier, a wash sale can happen if you buy a substantially identical investment within 30 days before or after the sale.

If you do tax-loss harvesting in your brokerage account and then buy a substantially identical investment in your IRA, Roth IRA, 401(k), 403(b), or any other type of account you own, you could trigger a wash sale.

Also, you need to coordinate with your spouse. You can’t buy a substantially identical investment in any of your spouse’s accounts.

After 30 days have passed, you can decide if you want to swap back to the original investment you had or continue with the similar investment.

Large Short-Term Capital Gain: If you have a large capital gain, you may not want to sell the similar investment to go back to the original. You may want to keep it.

Small Short-Term Loss: If the similar investment has a loss, you may want to sell it again and swap back to the original investment.

Small Short-Term Capital Gain: If you have a small short-term capital gain, that’s where it can get tricky. You may decide the similar investment is not ideal and you want to use up some of the losses you booked by selling the similar investment with the short-term capital gain. You may decide it’s close enough and keep it.

It depends on how closely it tracks, fees, taxes, and other factors.

Short-Term Gains and Losses vs. Long-Term Gains and Losses

One of the common questions that comes up is how short-term capital gains and losses offset long-term capital gains and losses.

Short-term losses occur when you do tax-loss harvesting with an investment held less than a year. Long-term losses occur when you do tax-loss harvesting with an investment held more than a year.

For example, if you bought an investment on April 1 and sold it on June 2 of the same year for a loss, it would be a short-term loss. If you bought an investment on April 1 and sold it on April 2 of the following year at a loss, it would be a long-term loss.

Important Note: First, short-term losses offset short-term capital gains, then long-term losses offset long-term capital gains and finally they can then offset each other.

This is an important order to understand because if you have short-term losses, you can use them to offset short-term capital gains. Since short-term capital gains are taxed at ordinary income tax rates and long-term capital gains are taxed at long-term capital gains rates, short-term losses are more valuable.

Example of Losses Offsetting Each Other

Let’s assume the following:

- Short-term capital loss of $40,000

- Short-term capital gain of $5,000

- Long-term capital loss of $4,000

- Long-term capital gain of $6,000

You first net the short-term losses and gains, bringing your short-term loss to $35,000 ($40,000 – $5,000).

Then, you net the long-term capital loss and gains, bringing your long-term capital gain to $2,000 ($6,000 – $4,000).

Then, you net them against each other, bringing your short-term loss to $33,000 ($35,000 – $2,000).

Assuming you had no other capital gains, you could use $3,000 to offset your ordinary income and carry forward $30,000 to next year. The nature of the loss, short-term or long-term carries forward, which means you would have $30,000 of short-term losses you can carry forward.

This is an important planning piece because you may want to avoid recognizing long-term capital gains, so you can use those short-term losses to offset future year short-term capital gains.

Risks of Tax-Loss Harvesting

Although tax-loss harvesting seems like a strategy almost everyone would want to use, there are risks to the strategy and people who may not want to use it.

Tax Rates Go Up for Capital Gains

One major risk to tax-loss harvesting is that tax rates for capital gains could go up in the future. Since you are deferring taxes with tax-loss harvesting and establishing a lower cost basis, it’s possible tax rates for capital gains go up and when you need to sell an investment later, you could pay a higher tax rate.

For example, if you tax-loss harvest the $100,000 investment previously talked about at $80,000, your new cost basis is $80,000. If you are in the 15% long-term capital gains tax bracket now and you are in a hypothetical 25% long-term capital gains tax bracket in the future, you could end up paying more. Let’s say the investment grew to $150,000 and you sold.

Had you not tax-loss harvested, you would have a $50,000 capital gain. Since you tax-loss harvested, you have a $70,000 capital gain. Assuming a hypothetical future 25% long-term capital gains rate, you would owe $17,500 in long-term capital gains taxes instead of $12,500.

You caused an extra $20,000 of capital gain that then is taxed at 25%, which is causing the extra $5,000 of long-term capital gains taxes.

I’ll be the first to say I have no idea where tax rates are headed – up, down, or sideways – but they have been different in the past.

It’s important to know you are trading a loss and potential tax benefit today for a future unknown tax amount.

Similar Investment Doesn’t Track As Well as Primary Investment

Another risk of tax-loss harvesting is that you either wait in cash and the market goes up or you invest in a similar investment that doesn’t track the index or asset class as well as you want.

For example, if you swap a fund that tracks the S&P 500 for a fund that tracks the Russell 1000, performance and risk may be slightly different than you originally intended because the Russell 1000 will include some mid-cap stocks, has a different filtering process for which stocks to include, and rebalances at different times.

In more extreme examples, the investment may not track closely or have very different methodologies of how they select investments.

Expense Ratio is Higher for the Similar Investment

Another risk of tax-loss harvesting is that you may need to select a similar investment with a higher expense ratio. If that happens, you may get stuck in the higher expense ratio fund if the market recovers and there is a large capital gain in the new investment you don’t want to recognize.

For example, if you have an investment with a 0.15% expense ratio and the similar investment you select has an expense ratio of 0.30%, but the market recovers and you have a short-term capital gain of $20,000 before you can swap back, you may not want to sell the new fund.

Now, you have a fund that costs double what you were originally paying that you don’t want to sell because you don’t want to recognize the capital gain.

If you had a $100,000 investment, that is a difference of $150 per year. It’s a minor issue, but could be a more significant problem if the expense ratio is significantly higher or it is a larger investment.

0% Capital Gains Bracket

Another risk of tax-loss harvesting is that it may not benefit certain people.

There are people who are in the 0% long-term capital gains bracket who may want to recognize long-term capital gains instead of capture losses. That my seem odd, but in certain tax situations, it can be better to recognize capital gains if it means paying no additional taxes.

If your income is low enough to put you in the 0% long-term capital gains bracket, there may be no benefit to doing tax-loss harvesting. You may only be lowering your cost basis without reducing your taxes.

If you can already recognize long-term capital gains and pay 0% in long-term capital gains taxes, there may be no point in recognizing losses.

Example of Tax-Loss Harvesting to Reduce Taxes

Let’s look at two examples of the benefits of tax-loss harvesting. One example will be a large capital gain from a home sale and another will be offsetting capital gains for portfolio withdrawals using a tax loss carryforward.

Example 1 – Home Sale

A home sale can be a big taxable event, particularly given the strength of the U.S. real estate market over the past decade.

For example, let’s say the following happened:

- You tax-loss harvested $400,000 in a brokerage account because the market dropped significantly.

- You sold your home and had a long-term capital gain that exceeded the home sale exclusion amount ($250,000 if single or $500,000 if married filing jointly)

You bought your house for $250,000 many decades ago, and it’s now worth $1,500,000. You were widowed four years ago and thought about selling the home then, but you decided to hold onto it for longer.

Widows may be able to sell within two years after a spouses death and still claim the $500,000 home sale exclusion amount, but since you are outside that window, you can only claim a $250,000 exclusion.

You have improvements that raise the cost basis of the home from $250,000 to $300,000. If you sold today for $1,500,000 and had a cost basis of $300,000, your long-term capital gain is $1,200,000. After the $250,000 home sale exclusion, the long-term capital gain is $950,000.

Assuming a 15% long-term capital gains rate on the full amount (in reality, it might be partially taxed at 15% and 20%), the long-term capital gains tax would be about $142,500.

If you didn’t tax-loss harvest and have $400,000 of losses, you would pay the full amount.

However, you did the tax-loss harvesting and can now offset some of the $950,000 long-term capital gain, bringing it to a long-term capital gain of $550,000. Assuming a 15% long-term capital gains rate, that is about $82,500 in long-term capital gains taxes.

The tax-loss harvesting helped you save about $60,000 in long-term capital gains taxes.

If you did the tax-loss harvesting correctly, you are still invested similarly, can participate in future market growth as you would have before, and you were able to reduce your tax bill by $60,000.

That’s the power of tax-loss harvesting!

Example 2 – Portfolio Withdrawals with Long-Term Capital Gains

In retirement, people often have to recognize capital gains to generate portfolio withdrawals for regular spending.

For example, let’s say the following happened:

- You tax-loss harvested $400,000 in a brokerage account because the market dropped significantly.

- You need to create about $40,000 in long-term capital gains each year to generate the portfolio withdrawals to support your spending.

A common problem in retirement is how to take withdrawals from investment in the most tax-efficient way. For people with brokerage assets, capital gains can add to their tax burden, but tax-loss harvesting could help.

Let’s say the market drops significantly, such as it did in 2008 and 2009. You booked $400,000 in losses through tax-loss harvesting, but your portfolio doesn’t have any capital gains, so you don’t use any of those losses in the current year.

You use $3,000 to offset ordinary income and carry forward $397,000 worth of losses. The next year your portfolio does have capital gains and you need to recognize $40,000 of long-term capital gains. You offset the $40,000 fully, which would normally be taxed at 15%, resulting in taxes of $6,000. You then use $3,000 to offset the ordinary income. If your marginal rate is 25%, you save about $750 in ordinary income taxes. Your loss carryforward is $354,000.

The same thing happens the next year. You recognize $40,000 in long-term capital gains to get the cash you need for withdrawals and offset $3,000 of ordinary income. Another $6,000 is saved in capital gains taxes and $750 in ordinary income taxes.

You continue this process every year for the next 9 years. During those 9 years, you avoided $360,000 in long-term capital gains and $30,000 of ordinary income. Over that time, that meant saving about $54,000 in long-term capital gains taxes ($360,000 times 15%) and $7,500 in ordinary income taxes ($30,000 times 25%). In total, you saved about $61,500 in taxes. You also have $10,000 left in losses that can be used.

When losses occur, it can be a good opportunity to book them and offset future capital gains for a long period of time to help with portfolio withdrawals in retirement or to help with rebalancing the portfolio.

Final Thoughts – My Question for You

Tax-loss harvesting can be a helpful strategy to defer taxes.

Unlike many tax strategies that can be done on an annual basis, tax-loss harvesting requires you to monitor your investment portfolio on a regular basis to take advantage of declines in the market as they occur to get the most benefit.

You should also pay careful attention to the rules around tax-loss harvesting to avoid a potential wash sale, as well as the risks of tax-loss harvesting. It doesn’t make sense for everybody, and the tax savings it provides will vary based on your individual tax situation.

I’ll leave you with one question to act on.

Will you implement tax-loss harvesting in your portfolio and if so, how?